Diabetes Distress Linked to Autonomic Symptoms in Adults Diabetes Distress Linked to Autonomic Symptoms in Adults

April 7, 2025Rhythm Pharma’s Drug for Rare Obesity Meets Late-stage Trial Goal Rhythm Pharma’s Drug for Rare Obesity Meets Late-stage Trial Goal

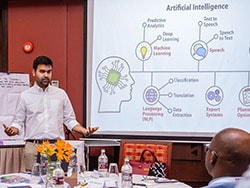

April 7, 2025Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming more embedded in the work life of some physicians who are taking the initiative to test its use in various scenarios.

“I use [generative AI] all the time,” Mohamed Elsabbagh, MBBCh, endocrinology consultant with Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust, Huddersfield, England, told Medscape Medical News. “I’m a big fan of it, and it has helped me a lot to find papers, summarize guidelines, or compare protocols.”

Mohammad Abdalmohsen, MBBS, a lung cancer fellow at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, told Medscape Medical News that he also uses generative AI, like ChatGPT, often. “If you give it very specific questions, it comes up with great answers. I just asked ChatGPT for a protocol that I couldn’t find, and it got it for me in 5 seconds.”

These experiences are not solitary ones.

The UK’s General Medical Council (GMC) released a qualitative research study in November last year in which a registrar in general practice explained that they use generative AI to create clinical scenarios to help mentor colleagues preparing for exams. An ophthalmologist said they use it to more quickly and professionally generate patient letters. To do this, they use a prompt that includes the basic text of a patient letter and add test and diagnostic findings to it. They proofread the AI-generated letter, copy it into an external document, and then add the confidential patient information that shouldn’t be shared with the tool. “That works very well because that enables you to produce, I think, stuff that’s a bit more consistent than you normally would be doing, and it’s better laid out than you normally would be doing,” they were quoted as saying in the report.

That study was a follow-up of a report published a month earlier, also commissioned by the GMC and conducted by The Alan Turing Institute, which studies public policy and AI. They surveyed doctors about their perspectives on three types of “AI systems”: Diagnostic and decision support systems that help clinical decision-making — like those that detect tumors in radiology scans — efficiency-focused systems that improve the allocation of resources, and generative systems like ChatGPT that can aid in the creation of text and images.

The report found that more than a quarter of the 929 UK-based doctors surveyed between December 2023 and January 2024 said they had made use of at least one type of AI system in their work in the last year. Of those that had reported using AI, more than half said they used it at least once a week, 16% reported using diagnostic and decision support systems, while a further 16% were using generative AI. Fewer doctors used systems aimed at improving efficiency, like for triaging.

Saba Esnaashari, a data scientist with The Alan Turing Institute’s public policy program, told Medscape Medical News that the proportion of doctors using these AI systems is likely to be much higher now, judging from more recent surveys she has conducted in the public sector.

AI isn’t just being used by doctors in the United Kingdom.

A study found that 87.1% of 1000 medical doctors licensed to practice in Portugal reported using AI in the daily management of their professional practice, for example, for writing electronic health records or to schedule and book appointments. Additionally, it found that, as early as 2023 when the research was done, 69.3% had no problem using AI to assist in defining therapeutic prescriptions, and 68% said they would use it to help make diagnoses. They were more divided, however, as to whether AI should assist in collecting a patient’s medical history.

Paul Hager of the Institute for AI and Informatics in Medicine at the Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, whose research group has evaluated generative AI clinical tools, said doctors are anecdotally using off-the-shelf applications for clinical decision-making. “We work here in the hospital, and you do hear of doctors using ChatGPT,” he explained. It is a natural evolution from Googling or looking up guidelines in paper form, he added.

Hager said that ChatGPT could be used by experienced clinicians, for example, who need to jog their memory with potential differential diagnoses when they are tired during a late-night shift and are faced with a patient presenting with several unique symptoms. Due to their experience, they will be able to determine which of the AI-suggested options makes the most sense.

Useful Tool but With Caveats

Could using AI for clinical decision-making cloud doctors’ judgment?

The Portuguese and Turing studies showed that most doctors don’t think this will be the case.

Esnaashari said doctors reported that they would be more likely to ask colleagues if AI produced a different answer from what they were expecting or proceed using their own clinical judgment. “They said they would basically investigate more if AI diagnosis is different from their own perception. And 15% said that they would just ignore it,” she said. Only 1% said that they might trust AI over their own experience and training.

Hager agrees that using AI as a tool in clinical practice tends to lead to better decisions. He is worried, however, that junior or less experienced clinicians might “just blindly follow what’s coming out. They don’t know how to differentiate a good answer from a bad answer.”

Institutions Hop Onboard AI Train

Generative AI is not only being tested for clinical practice at the individual level.

Google is testing Articulate Medical Intelligence Explorer, which has been designed to diagnose medical conditions through a text-based conversation.

In Kenya, a trial of a generative AI system is already underway — although the system is not designed for doctors but for clinical support staff that are employed in low-resource, rural settings. Acting like a copilot during patient consultations, it recognizes text added to electronic health records, such as symptoms, possible diagnoses, blood tests, prescriptions, and treatment plans. It checks the text using a large language model (LLM) based on OpenAI’s GPT-4 and suggests alternative diagnoses or treatments if it sees fit. “It has learnt about clinical information. It’s doing everything from reading those symptoms and reconciling whether those symptoms match with the diagnosis that the clinician is recording,” said Bilal Mateen, MBBS, MPH, PhD, chief AI officer at PATH, a nonprofit global health innovation funder and part of the consortium managing the trial, which includes Pender, a social enterprise that runs the clinics, and Moi University. PATH is working on AI clinical decision-making systems in Nigeria and Rwanda too.

But while generative AI on the basis of LLMs is sophisticated, most aren’t quite ready for implementation, warned Hager, whose group has discovered several areas that still need development. One example, he said, is that when the same information is input into an LLM in different orders, suggestions can be different.

Some doctors featured in the GMC report appear to be aware of AI’s flaws.

As a consultant psychiatrist said, “So large language models, with all the refinements, GPT-4.0, still produce all sorts of nonsense quite quickly…That’s why you end up with all of these strange outputs and hallucinations.”

Mateen, Elsabbagh, Abdalmohsen, Esnaashari, and Hager reported no relevant financial relationships. The Kenyan trial is funded by the Gates Foundation. Mateen is the principal investigator on the award and reported no relevant financial relationships.